Campos vectoriales en diferentes sistemas

De Laplace

(→Tercer campo) |

(→Tercer campo) |

||

| Línea 83: | Línea 83: | ||

<center><math>\mathbf{C}=2r^2\cos\theta\,\mathrm{sen}\,\theta(\mathrm{sen}\,\theta\mathbf{u}_{r}+\cos\theta\mathbf{u}_{\theta})- | <center><math>\mathbf{C}=2r^2\cos\theta\,\mathrm{sen}\,\theta(\mathrm{sen}\,\theta\mathbf{u}_{r}+\cos\theta\mathbf{u}_{\theta})- | ||

| - | r^2(\mathrm{sen}^2\theta-\cos^2\theta)(\cos\theta\mathbf{u}_{r}-\mathrm{sen}\,\theta\mathbf{u}_{\theta}) | + | r^2(\mathrm{sen}^2\theta-\cos^2\theta)(\cos\theta\mathbf{u}_{r}-\mathrm{sen}\,\theta\mathbf{u}_{\theta}) |

=r^2\cos\theta\mathbf{u}_{r}+r^2\mathrm{sen}\,\theta\mathbf{u}_{\theta}</math></center> | =r^2\cos\theta\mathbf{u}_{r}+r^2\mathrm{sen}\,\theta\mathbf{u}_{\theta}</math></center> | ||

Revisión de 15:15 25 sep 2008

Contenido |

1 Enunciado

Exprese los siguientes campos vectoriales en coordenadas cartesianas, cilíndricas y esféricas:

2 Solución

2.1 Primer campo

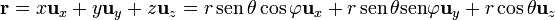

Para expresar el vector de posición en diferentes sistemas coordenados, lo más simple es aplicar que se trata de un gradiente, tal como se ve en otro problema.

Otra posibilidad es el cálculo directo. Por ejemplo, para expresar este vector en coordenadas esféricas, escribimos en primer lugar las componentes cartesianas en función de las coordenadas esféricas

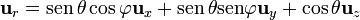

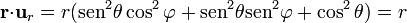

A continuación, multiplicamos por cada uno de los vectores de la base, expresados también en sus componentes cartesianas. La componente radial es

La componente polar se anula

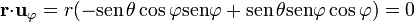

Lo mismo ocurre con la componente acimutal

\] por lo que la expresión final es el conocido

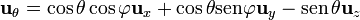

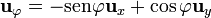

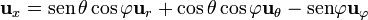

Una posibilidad adicional de cálculo directo consiste en, tras sustituir las componentes cartesianas por su expresión esféricas, expresar los vectores de la base cartesiana como combinación lineal de los vectores de la base en esféricas. Así, por ejemplo,

Operando después con los coeficientes de cada vector de la base esférica se llega a la expresión buscada.

2.2 Segundo campo

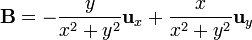

Para el campo

podemos sustituir la definición de las coordenadas cilíndricas

y obtener

el vector que aparece entre paréntesis no es otro que  por lo que

por lo que

En esféricas tenemos que, dado que

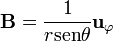

y que  es el mismo en los dos sistemas,

es el mismo en los dos sistemas,

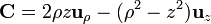

2.3 Tercer campo

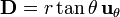

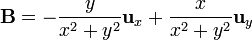

Para poner este vector en cartesianas tenemos que

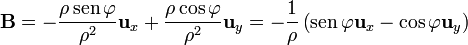

y para pasarlo a esféricas resulta