4.8. Rodadura permanente de un disco

De Laplace

Contenido |

1 Enunciado

La rodadura permanente de un disco de radio R sobre una superficie horizontal puede describirse mediante el campo de velocidades

donde la superficie horizontal se encuentra en y = − R.

- Determine, para un instante dado, la velocidades de los puntos A, B, C y D situados en los cuatro cuadrantes del disco.

- Suponiendo

, calcule la aceleración de dichos puntos para el mismo instante.

, calcule la aceleración de dichos puntos para el mismo instante.

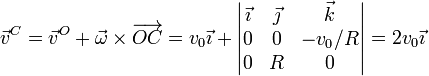

2 Velocidades

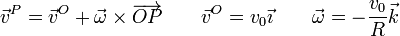

Para cada uno de los puntos, basta aplicar la fórmula correspondiente

- Punto A

- Su vector de posición relativa es

- por lo que su velocidad vale

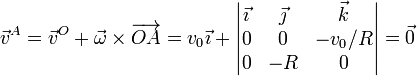

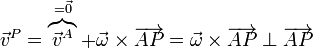

- Punto B

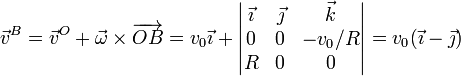

- Punto C

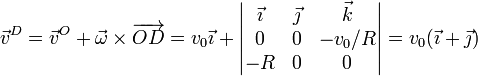

- Punto D

Obtenemos que el punto de contacto con el suelo posee velocidad instantánea nula, mientras que el punto superior posee velocidad doble a la de avance de la rueda.

Las velocidades de los puntos O, B, C y D son perpendiculares al vector de posición relativo al punto A, como corresponde a que este se encuentre en el eje instantáneo de rotación:

3 Aceleraciones

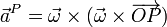

La expresión general del campo de aceleraciones es

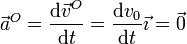

En este caso tenemos que la velocidad del punto O es constante, por lo que

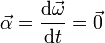

También es nula la aceleración angular

lo que nos deja con

Desarrollando el doble producto vectorial

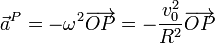

Para los cuatro puntos del enunciado, el vector de posición relativo al punto O está contenido en el plano OXY y es por tanto perpendicular a la velocidad angular, con lo que la aceleración de cada uno se reduce a

En los cuatro casos resulta radial y hacia adentro del disco, lo que nos da las cuatro aceleraciones