No Boletín - Otro tiro parabólico (Ex.Sep/15)

De Laplace

1 Enunciado

Un proyectil se mueve en el plano vertical  . Se conoce su aceleración constante (debida a su propio peso), y también su posición y su velocidad en el instante inicial (

. Se conoce su aceleración constante (debida a su propio peso), y también su posición y su velocidad en el instante inicial ( ):

):

![\vec{a}(t)=-g\,\vec{k}\,\,\,;\,\,\,\,\,\,\,\,\,\,\,\,\vec{r}(0)=h\,\vec{k}\,\,\,;

\,\,\,\,\,\,\,\,\,\,\,\,\vec{v}(0)=v_0\,[\,\mathrm{cos}(\theta)\,\vec{\imath}+

\mathrm{sen}(\theta)\,\vec{k}\,]](/wiki/images/math/d/e/9/de9c3ce06bffd9ab7a69070c76c7c6b8.png)

donde  ,

,  y

y  tienen valores positivos, y

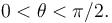

tienen valores positivos, y  está comprendido en el intervalo

está comprendido en el intervalo

- Determine el radio de curvatura de la trayectoria del proyectil en el instante inicial.

- Determine la celeridad del proyectil en el instante en el que su trayectoria corta al eje

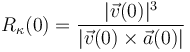

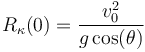

2 Radio de curvatura en el instante inicial

El radio de curvatura de la trayectoria del proyectil en el instante inicial puede calcularse a partir de su velocidad y su aceleración en dicho instante mediante la fórmula:

Así que, sustituyendo en dicha fórmula los valores iniciales de velocidad y aceleración:

![\vec{v}(0)=v_0\,[\,\mathrm{cos}(\theta)\,\vec{\imath}+

\mathrm{sen}(\theta)\,\vec{k}\,]\,\,\,;\,\,\,\,\,\,\,\,\,\,\,\,\vec{a}(0)=-g\,\vec{k}](/wiki/images/math/c/7/0/c70d37c929961513dc146c824085b322.png)

se obtiene:

3 Celeridad del proyectil al cortar el eje OX

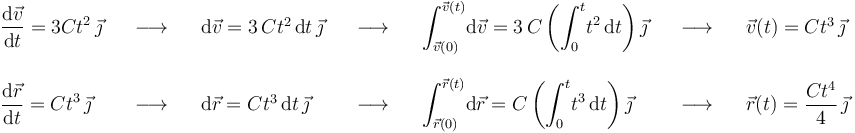

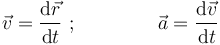

Las definiciones de velocidad instantánea y aceleración instantánea establecen que:

En el caso que nos ocupa, conocemos los valores iniciales de la posición  y de la velocidad

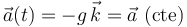

y de la velocidad  del proyectil, y además conocemos su aceleración en todo instante, la cual tiene valor constante:

del proyectil, y además conocemos su aceleración en todo instante, la cual tiene valor constante:

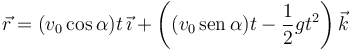

Determinar la velocidad y la posición del proyectil para  se reduce a integrar la aceleración una y dos veces, respectivamente, entre el instante inicial y un instante genérico:

se reduce a integrar la aceleración una y dos veces, respectivamente, entre el instante inicial y un instante genérico:

![\begin{array}{lllll} \mathrm{d}\vec{v}=\vec{a}\,\mathrm{d}t & \,\,\,\,\,\longrightarrow\,\,\,\,\, & \displaystyle\int_{\vec{v}(0)}^{\vec{v}(t)}\!\mathrm{d}\vec{v}=\vec{a}\displaystyle\int_{0}^{t}\mathrm{d}t & \,\,\,\,\,\longrightarrow\,\,\,\,\, & \vec{v}(t)=\vec{v}(0)+\vec{a}\,t \\ \\

\mathrm{d}\vec{r}=[\vec{v}(0)+\vec{a}\,t\,]\,\mathrm{d}t & \,\,\,\,\,\longrightarrow\,\,\,\,\, & \displaystyle\int_{\vec{r}(0)}^{\vec{r}(t)}\!\mathrm{d}\vec{r}=\vec{v}(0)\displaystyle\int_{0}^{t}\mathrm{d}t+\vec{a}\displaystyle\int_{0}^{t}\!t\,\mathrm{d}t & \,\,\,\,\,\longrightarrow\,\,\,\,\, & \vec{r}(t)=\vec{r}(0)+\vec{v}(0)\,t+\displaystyle\frac{1}{2}\,\vec{a}\,t^2\end{array}](/wiki/images/math/6/e/0/6e0676e651b289f2276a3698e3c4bb9d.png)

Sustituyendo los valores dados de  y

y  , obtenemos:

, obtenemos:

![\vec{v}(t)=v_0\,\mathrm{cos}(\theta)\,\vec{\imath}+\left[v_0\,\mathrm{sen}(\theta)-g\,t\right]\vec{k}\,\,\,;\,\,\,\,\,\,\,\,\,\,\,\,\vec{r}(t)=v_0\,\mathrm{cos}(\theta)\,t\,\vec{\imath}+\left[h+v_0\,\mathrm{sen}(\theta)\,t-\displaystyle\frac{1}{2}\,g\,t^2\right]\vec{k}](/wiki/images/math/5/7/7/577f65674580d528587a68747f835ba0.png)

lo que nos da el vector de posición en cada instante

Derivando el vector de posición respecto al tiempo obtenemos la velocidad intantánea

%%% Conforme a las definiciones de velocidad instantánea y aceleración instantánea, podemos escribir:

Conocemos también las condiciones iniciales de posición y velocidad:

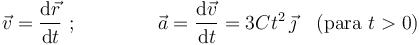

Por tanto, determinar la velocidad y la posición de la partícula para  se reduce a integrar la aceleración una y dos veces, respectivamente, entre el instante inicial y un instante genérico:

se reduce a integrar la aceleración una y dos veces, respectivamente, entre el instante inicial y un instante genérico: