1.10. Volumen de un paralelepípedo

De Laplace

(→Segundo volumen) |

(→Segundo volumen) |

||

| Línea 61: | Línea 61: | ||

y que el producto vectorial de <math>\overrightarrow{OA}</math> por cualquier cosa es ortogonal a <math>\overrightarrow{OA}</math> llegamos a | y que el producto vectorial de <math>\overrightarrow{OA}</math> por cualquier cosa es ortogonal a <math>\overrightarrow{OA}</math> llegamos a | ||

| - | <center><math>\left(\overrightarrow{OA}\times\overrightarrow{OB}\right)\cdot\left(\overrightarrow{OC}-\overrightarrow{OA}\right) = \left(\overrightarrow{OA}\times\overrightarrow{OB})\cdot\overrightarrow{OC}</math></center> | + | <center><math>\left(\overrightarrow{OA}\times\overrightarrow{OB}\right)\cdot\left(\overrightarrow{OC}-\overrightarrow{OA}\right) = \left(\overrightarrow{OA}\times\overrightarrow{OB}\right)\cdot\overrightarrow{OC}</math></center> |

Concluimos entonces que | Concluimos entonces que | ||

Revisión de 11:44 25 sep 2010

Contenido |

1 Enunciado

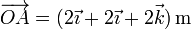

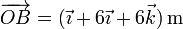

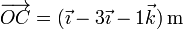

Sean los puntos de coordenadas (en el SI) O(1,0,2), A(3,2,4), B(2,6,8) y C(2, − 3,1). Determine el volumen del paralelepípedo definido por los vectores  ,

,  y

y  .

.

Halle del mismo modo el volumen del paralelepípedo definido por los vectores  ,

,  y

y  .

.

Calcule igualmente el volumen del tetraedro irregular definido por estos cuatro puntos.

2 Primer volumen

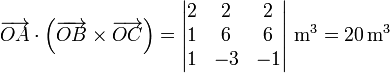

El volumen de un paralelepípedo se calcula como el producto mixto (sin signo) de los tres vectores que definen el paralelepíedo.

En nuestro caso los vectores los obtenemos hallando las diferencias entre las coordenadas de cada par de puntos

de forma que el producto mixto lo da el determinante

Al ser positivo, este es el volumen del paralelepípedo.

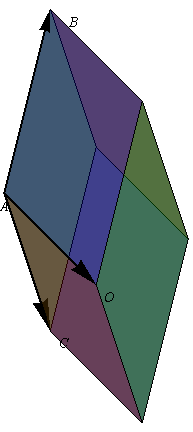

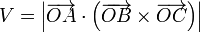

3 Segundo volumen

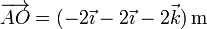

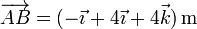

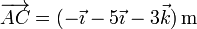

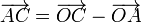

Para el segundo paralelepípedo calculamos los nuevos vectores de posición relativos

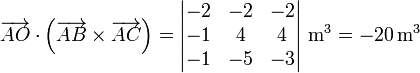

El nuevo producto mixto es

Puesto que el volumen debe ser positivo obtenemos

Este es el mismo resultado que antes, pese a que geométricamente estemos hablando de un paralelepípedo diferente. Puede demostrarse en general: un paralelepípedo definido por cuatro puntos a partir de tres vectores concurrentes que unen uno de los puntos con los otros tres posee el mismo volumen sea cual sea el punto de los cuatro que tomemos como origen de los vectores.

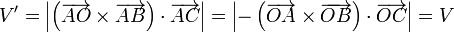

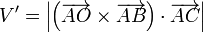

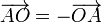

Para este caso la demostración parte de

aplicando que

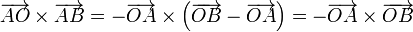

nos queda, para el primer producto vectorial

ya que el producto vectorial de un vector por si mismo es nulo. Aplicando ahora que

y que el producto vectorial de  por cualquier cosa es ortogonal a

por cualquier cosa es ortogonal a  llegamos a

llegamos a

Concluimos entonces que