1.12. Ejemplo de construcción de una base

De Laplace

(→Segundo vector) |

(→Segundo vector) |

||

| Línea 50: | Línea 50: | ||

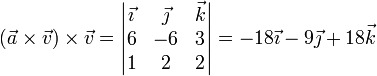

<center><math>(\vec{a}\times\vec{v})\times \vec{v}=\left|\begin{matrix}\vec{\imath} & \vec{\jmath} & \vec{k} \\ 6 & -6 & 3 \\ 1 & 2 & 2 \end{matrix}\right|=-18\vec{\imath}-9\vec{\jmath}+18\vec{k}</math></center> | <center><math>(\vec{a}\times\vec{v})\times \vec{v}=\left|\begin{matrix}\vec{\imath} & \vec{\jmath} & \vec{k} \\ 6 & -6 & 3 \\ 1 & 2 & 2 \end{matrix}\right|=-18\vec{\imath}-9\vec{\jmath}+18\vec{k}</math></center> | ||

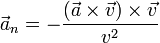

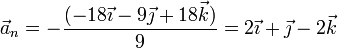

| - | Dividiendo por el módulo de \vec{v} al cuadrado y cambiando el signo obtenemos la componente normal | + | Dividiendo por el módulo de <math>\vec{v}</math> al cuadrado y cambiando el signo obtenemos la componente normal |

<center><math>\vec{a}_n = -\frac{(-18\vec{\imath}-9\vec{\jmath}+18\vec{k})}{9}=2\vec{\imath}+\vec{\jmath}-2\vec{k}</math></center> | <center><math>\vec{a}_n = -\frac{(-18\vec{\imath}-9\vec{\jmath}+18\vec{k})}{9}=2\vec{\imath}+\vec{\jmath}-2\vec{k}</math></center> | ||

Revisión de 16:03 7 sep 2010

Contenido |

1 Enunciado

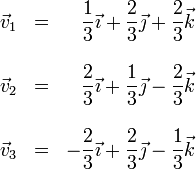

Dados los vectores

Construya una base ortonormal dextrógira, tal que

- El primer vector vaya en la dirección de

- El segundo esté contenido en el plano definido por

y

y

- El tercero sea perpendicular a los dos anteriores, y orientado según la regla de la mano derecha.

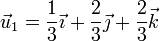

2 Primer vector

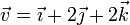

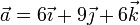

Obtenemos el primer vector normalizando el vector  , esto es, hallando el unitario en su dirección y sentido, lo que se consigue dividiendo este vector por su módulo

, esto es, hallando el unitario en su dirección y sentido, lo que se consigue dividiendo este vector por su módulo

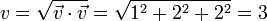

Hallamos el módulo de

por lo que

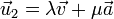

3 Segundo vector

El segundo vector debe estar en el plano definido por  y

y  , por lo que debe ser una combinación lineal de ambos

, por lo que debe ser una combinación lineal de ambos

además debe ser ortogonal a  (y por tanto, a

(y por tanto, a  )

)

y debe ser unitario

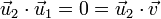

El procedimiento sistemático consiste en hallar la componente de  normal a

normal a  y posteriormente normalizar el resultado.

y posteriormente normalizar el resultado.

La proyección normal la calculamos con ayuda del doble producto vectorial

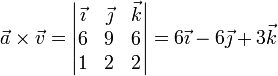

Calculamos el primer producto vectorial

Hallamos el segundo

Dividiendo por el módulo de  al cuadrado y cambiando el signo obtenemos la componente normal

al cuadrado y cambiando el signo obtenemos la componente normal

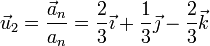

Normalizando esta cantidad obtenemos el segundo vector de la base

4 Tercer vector

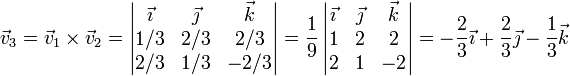

El tercer vector lo obtenemos como el producto vectorial de los dos primeros

Por tanto, la base ortonormal dextrógira está formada por los vectores